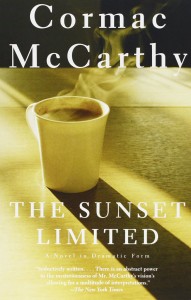

I don’t think it would be a stretch to call Cormac McCarthy one of our era’s greatest American writers. He has certainly carried the torch of a variety of writers that came before him, from Hemingway to O’Connor. McCarthy is known for his stripped down prose, and The Sunset Limited takes it even a step further.

I don’t think it would be a stretch to call Cormac McCarthy one of our era’s greatest American writers. He has certainly carried the torch of a variety of writers that came before him, from Hemingway to O’Connor. McCarthy is known for his stripped down prose, and The Sunset Limited takes it even a step further.

If you have read The Road, Child of God, or any of his other books, then you know that McCarthy works as a mechanical minimalist. He uses only the sparsest punctuation and avoids dialogue tags whenever possible. His style is gritty, realistic, and grotesque in a wonderful Southern Gothic sense.

The Sunset Limited has the usual bleak McCarthy tone, but is written entirely in dramatic form. This is essentially a play script. However, its stage directions are more sparse than most plays. Really, the format seems to be McCarthy challenging himself. Whereas a lot of his novels force him to write so tight that there is no doubt who is speaking, regardless of notation, this seems to be an experiment in stripping a novel down to dialogue only.

The plot is pretty straight forward. White, a nihilistic, atheist professor goes to “catch a ride on the Sunset Limited.” By catch a ride, he means throw himself onto the tracks in front of the oncoming train. He is saved from his suicide by Black, an uneducated but devout ex-con. The only set is Black’s apartment. For the most part, the two men sit opposite of each other and debate.

White’s goal is simple: to leave the apartment and catch the next Sunset Limited. Black’s goal is also simple: to keep White from doing so.

This doesn’t seem like the sort of narrative that would carry 170 pages, but White’s inability to be rude and his desire to be understood keeps him chained to the chair in a way that life itself can’t. Ending his life is one thing, but doing it without class seems to be something entirely different.

Black wants to save the professor, but you begin to wonder just whose salvation is on the line. Is it the atheist professor who is willing to throw himself in front of a train, believing that nothing awaits him upon death, or the devout ex-con who seems to define himself by those he saves. The debates go back and forth, and depending on what sort of person the reader is, he likely connects to something said by one or both.

McCarthy’s characters cover a lot of philosophical ground, definite extremes of both. I read the book during the whole government shutdown crisis. Black and White represent opposing ideologies, both maintaining absolute certainty that theirs is correct. It might remind you of a certain branch of the government.

In the end…well, I won’t ruin it, but if you know McCarthy, you can expect it is not warm and fuzzy. This one does not end with hugs and cake. But it is brilliant, easy to read, and will make you think. As an experiment with narrative form, it is an absolute success, much like most of McCarthy’s work.

Leave a Reply