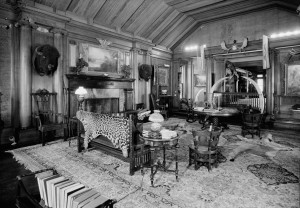

Trophy Room — November, 1928

I walked into the room expecting to see some sign of my host. Instead, a horde of dead eyes stared back at me. The firelight played off mounted heads: buffalo, deer, bear, and wolf. In the upper corner, an owl looked down with wings and talons outstretched. Above the mantle, an eight-foot long swordfish had been mounted, frozen in mid-leap. In the corner by the door stood a large cat, one of the mountain lions so prevalent in the Americas.

Outside, a cold November wind blew, howling around the mansion. The taxi ride from the station had been fraught with peril as we plunged along on icy roads packed with snow. Upon my arrival at Straeon Manor, the butler took my bags and showed me to my room. Dinner, he said, would be at eight o’clock, but my host wished to meet for drinks beforehand. I had taken time to clean up and rest from my travels. Then I dressed for dinner and arrived as instructed at the appointed hour.

I moved among the trophies and soft leather furniture toward the fireplace. The warmth was welcome and made me feel more at ease. A wireless set stood on a table beside one of the chairs. From the RCA Radiola came the happy strains of a ragtime melody I had not heard in years. The music warmed my heart as the fire warmed my bones.

I put down the gift I had brought for my old friend and noted with some joy the volume on his end table. From the looks of things, he was reading my new book: Mysteries of the Far East. Perhaps he had left it out for show.

I wondered if he was truly interested in my work when my eye traveled to the books lining the south wall — row upon row of books, a library of the supernatural and metaphysical. He had books on spiritualism, necromancy, fortune telling, spirit healing and the occult. I saw tomes about monsters, fairies, and folklore, witches and demons. Volumes of arcana so obscure, only one as well-versed as I understood their importance and their value. And alongside these fantastic books were copies of my works. He owned every text, from my expeditions in Burma and Nepal, to my excursions to deepest, darkest Africa. I removed a volume and studied it, and it became clear to me that these were not for show. This book had been read multiple times from the looks of the pages.

As I slipped the book back into its place on the shelf, the door opened and a familiar face greeted me with a smile.

“Sir Giles! Look at you! You haven’t aged a day since the war.”

I moved across the room to shake the man’s hand, but a handshake would not do. I embraced the large man in a hug and he in turn nearly lifted me from the floor.

“So good to see you, James,” I said. “You’re looking well.”

“Being near you is a tonic, my friend. I feel 10 years younger at the sight of your face.”

Since the Great War, James had aged considerably. He had always been my senior, in age and rank. Now, as I took in the sight of him, I noted a walking stick I had not seen before.

“What is that old thing?” I said, pointing at the cane.

“I use this for fending off the ladies,” he said, dismissively. “Can’t have the missus getting jealous when I go out for my morning constitutional.”

“I hope you don’t try walking in this weather,” I said. “I’ve seen less snow in the Himalayas.”

James ushered me to a chair and propped his cane against the one opposite it. He poured us a couple of drinks from the side bar, and sat in the chair beside me. I picked up the large package that was sitting between us and offered it to him.

“What’s this?”

“A thank you for your hospitality. I thought you might like to add it to your collection.”

Putting his drink on the table, he accepted the gift. He untied the string and removed the heavy brown paper around the box. He lifted the lid. His eyes grew wide.

“It’s a trophy from my latest expedition. Have you ever seen a foot that size?”

“The monster must be massive,” he said.

“We estimate somewhere between eight and twelve feet tall. That is all that’s left from a large trap we set outside our camp one night. The thing howled like mad, you should have heard it. But it was dark, and snowing like a blizzard. We couldn’t see a thing. In the morning, we found that. The animal must have ripped it off to get free.”

“What kind of beast is it?”

“I’m not sure. I’ve heard stories from the locals, but no one from the Western world has seen one and lived to tell the tale. Natives of the Himalayan region call them Meh-The or Yeti. They are described as man-bears that walk on two legs. I think they may be a variety of ape as yet unknown.”

“This is amazing,” said James. “But I can’t accept this. It belongs in a museum.”

“The curators I have offered it to wouldn’t take it. Without proper classification, it’s an oddity but nothing more. Even the Royal Academy wouldn’t take it.”

“I know some fellows at the university who would be keen to examine this,” said James.

“Just so they don’t dissect it and leave you with nothing. I want this to be here, among your trophies.”

He grunted at that. “Compared to this, those mounted heads are just silly decorations. This is a wonder, Giles. A true phenomenon.”

We toasted one another and drank the scotch as a quieter, more somber tune came on the radio. It reminded me of France at the end of the war, when James and I had said our goodbyes. His regiment was returning to America, as mine would soon be going back to England. Neither of us wanted to admit that we had enjoyed our time together. With all the death we had seen and all the friends we had lost, we had found camaraderie in one another’s company.

James had been like a big brother to me. A veteran of two campaigns, he took me under his wing when my regiment arrived on the line. I was a fresh recruit, barely old enough to shave. He called me Sir Giles, though I had been given no such honor. He and his Yankee rabble all loved a joke at we Brits’ expense. It was good to have something to laugh about, even if it was senseless.

During our brief time in the war, he saved my life countless times. And I had saved his. The trenches had been a violent and brutal rite of passage, and when I emerged I was a man. We left the battlefield as more than friends. We were brothers.

I had gone home to England and attended university, but it was no longer the life for me. Instead, my studies took me abroad, where I learned everything I could from anyone who would teach me. I learned biology, zoology, chemistry, and physics. I studied the heavens and the earth. I traveled to the most remote locations and sought wisdom from shaman and gurus.

When James sent me a telegram asking me to come, I could not say no. He needed me and my peculiar expertise, so I came at once.

“Your home is quite lovely,” I said, hoping to lighten the mood. “Do promise you’ll show me around after dinner.”

“Certainly,” he said. “I only wish we had more favorable weather. The gardens are lovely in the summertime. I’m afraid Straeon Manor is a bit inhospitable in winter.”

“A warm fire is all the hospitality I need,” I said. “Along with a fine scotch.”

We toasted each other again and laughed.

“I hope you don’t mind,” said James. “Lizzie is making her roasted chicken and dumplings.”

“I am always grateful for a home-cooked meal,” I told him.

“You won’t be after tonight!” And we laughed again.

While I had been off adventuring around the globe for the past decade, James had married and gone to work for Lizzie’s father. From his letters, it seemed that James was all but running the company now. With Lizzie had come Straeon Manor, a wedding present from her grandfather. And a short year later had brought Eliza, their daughter.

“Tell me about Eliza,” I said, hesitant to broach the subject.

James looked nervous and set aside his glass. He closed the box on his lap and set it on the floor. I could tell he had no desire to start this conversation, and it pained me to see him hurting so.

“Maybe after dinner,” I suggested.

“No,” he said. “You deserve to know now.”

Before he could continue, however, there was a knock on the door. The door swung open and a little girl no more than eight years old bounded into the room. Her green dress brought out the color of her eyes. The light from the fireplace made her hair seem aflame. Red and green, she was Christmas joy in a small, smiling package. And from the look on her father’s face, she was the apple of his eye.

“Momma asked me to come and bring you to dinner,” she said.

“Very well, my sweet. Tell her we shall be along directly.”

She turned to me and offered a small curtsey. “Are you Mr. Noble?”

“Yes, I am. And you must be Eliza. It is a pleasure to meet you.”

She reached out her hand and I took it without thinking. My calloused hand engulfed her small one, so soft and delicate. On contact, she stiffened, like a jolt of electricity had gone through her. And her eyes rolled back into her head. I thought she would fall, from being in this state. But she stood perfectly still.

“An epileptic seizure?” I asked. I had seen several cases in Africa, where those similarly afflicted were often considered possessed by demons. But we had been able to help calm those seizures with Western medicine. I wondered if James had access to phenobarbital.

“No,” said James. “It’s more than that.”

I didn’t understand, but made preparations to lay the girl out on the floor should she begin to convulse. I knew from experience that convulsions often brought with them a different kind of danger to the epileptic.

Eliza breathed in deeply, as if gasping for air. I thought she might be choking, but the next instant she began to speak in a deeper voice that was clearly not her own:

“In ten moons comes a cataclysm for those who worship Mammon.

It crashes without a sound, but all will know the idol has fallen.

A great sadness will cross the land, turning fruited fields to dust.

Man and child will know hunger and want.”

James looked at me with eyes pleading, silently questioning that which he could not discuss by telegram or even ask in private confidence.

The books in his library now made sense. He had been immersed in metaphysics in an attempt to explain what was happening to his daughter. Had he found something in those texts that led him to me, or was I merely a last desperate hope?

Eliza shook free of my grasp and raised her hands above her head. The strange voice continued:

“I see a great war, in ten years time, a conflict so great as to engulf all other wars.

Behemoths will move across the land and ships will fill the skies.

Fire will fall on Avalon. Women and children will cry for peace.

Death will come for all, until a cloud shall make twin suns appear.”

“Is she prophesying?” I asked.

“Yes,” said James. “I think so. She speaks in riddles. I don’t know what it means.”

“Write it down,” I said. And as I said that, she began to speak, repeating what she had said before. James grabbed a nearby notebook and began scribbling as she recited it again.

When she had repeated her words three times, fair Eliza slumped into my arms. I lifted her and set her onto a loveseat where she seemed to sleep. Lizzie came into the room just then, and her eyes grew wide with fright. She moved to her husband and grabbed him tightly.

“How long has this been happening?” I asked.

“About a year, now,” said James. “At first it was just the seizure, and we thought she might have contracted a fever. But when she began speaking — when that voice began speaking through her — I knew this was no mere illness.”

“So you’ve been reading,” I said, gesturing to his books. “And have you found anything?”

“Nothing specific. Legends of demons and devils speaking through the possessed. You have traveled so much and seen so many wonders, I contacted you in hopes that you might be able to help.”

“I’m afraid this is a bit out of my bailiwick. I’ve run into a few conjurers and gurus who could put themselves into such a trance. I even met a chap in India who claimed a spirit guide from the next world spoke through him. But I have never seen it happen to someone against their will, let alone a child.”

At this Lizzie began to cry. She cleaved to James and held her face against his jacket. I could see the stress of the past year had been hard on both of them. I wanted to offer them some measure of comfort, but I had come to this unprepared.

“I will do everything in my power to assist you,” I said. “But it will take time. For now, the best we can do is make her comfortable.”

“She’ll sleep through the night,” said James. “These spells usually sap her strength and leave her weak. When she awakes in the morning, she won’t remember a thing.”

“That’s probably for the best,” I said, wondering what help she could give us if she could remember — or what horrors such a memory would inflict on her.

“Come,” said Lizzie, composing herself once again. “Dinner is getting cold and we must eat.”

James slipped a pillow under Eliza’s head and drew a blanket up to her chest. He kissed her ever so lightly on her forehead and turned to go.

“I’m glad you’re here, Giles. I wish it were under better circumstances.”

“We’ve been through worse,” I said, patting his back. He picked up his walking stick and leaned heavily upon it.

As we left the room, I looked at the trophies mounted everywhere. From fish and fowl to all creatures great and small.

And I had the oddest feeling that something was watching us.

Leave a Reply