W. Someset Maugham has been credited with stating “Write what you know.” He also has been quoted as say, “There are three rules for writing the novel. Unfortunately no one knows what they are.”

Sounds as if he might have had his good days and bad days in the creative process, too. And not only that, his edict to “write what you know” has been misused by many composition teachers and abused by their students who seem to prefer the second quote …

Nevertheless, I write what I know. And then I slip into my “what if …?” mode, steal from every single author I’ve read and every person I’ve known, and assemble my stories out of bits and pieces, and what I end up with is a jigsaw-puzzle-like story of life.

Most of my characters are assimilation and assemblages, but a few of them are directly based on one or two people I’ve known, at least at the beginning of their “lives” in my novels, until they take off on their own while I follow them and jot down their exploits in “What if …? Land”. What if I gave the sunny-faced girl I remember from my first period Junior English class more responsibility than she can handle? What if I dropped a black basketball player into a small town and forced him to play football? What if I placed a metal detector into the hands of a gay kid and sent him to the scene of a crime sixty years ago? What if I killed almost everyone off except for a teenager who has run away from home and manages to find a place of safety?

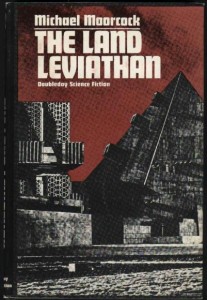

Author influences on me are many and varied, but most of them are from the first books I read while growing up. Walter R. Brooks taught me how to generate humor in his “Freddy the Pig” series as did Hugh Lofting in the Dr. Dolittle novels. Nevil Shute showed me how to create happy endings that could be both satisfying and believable. Robert A. Heinlein was at least the first writer to create living, breathing creatures for me, and his contemporary, Arthur C. Clarke, taught me how to create settings that never existed out of what I knew, or at least suspected. Mackinlay Kantor and Jan de Hartog showed me how to create alternate histories and populate them with almost-real characters. And the list goes on.

So – write what you know, but then be prepared to break any and all rules of writing. Works for me!