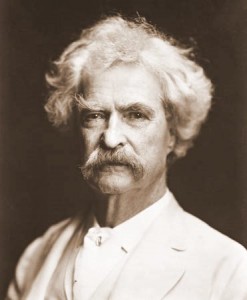

“…we are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants, so that we can see more than they…not by virtue of any sharpness of sight on our part…but because we are carried high and raised up by their giant size.” – John of Salisbury, paraphrasing Bernard of Chartes

Writers are readers, so I have been told. Indeed, every writer I know reads with an insatiable appetite for the written word in all its flavors. You can learn a lot from the writers of the past. They allow you to sit upon their broad shoulders and learn from their experience.

Writers are readers, so I have been told. Indeed, every writer I know reads with an insatiable appetite for the written word in all its flavors. You can learn a lot from the writers of the past. They allow you to sit upon their broad shoulders and learn from their experience.

There are many things to learn in writing. I’ve quoted Hemingway before that we are all apprentices in a craft with no masters. That is true. You could write from the first day of your literacy to the last day of your life and you will never know everything.

You can write a million words, and still a million more will be waiting. All you can do is learn and write.

That being said, different writers have given me different things.

I’ve mentioned Ray Bradbury’s book Zen in the Art of Writing several times as being a major influence on me. Bradbury has a love of writing that is infectious. You can taste the love in his writing. But there are also things to be learned in that book. First, you have to write. There is no other way to be a writer than to write. Second, just because you don’t know what to write, doesn’t mean you can’t write. Sometimes I use a technique I learned from Bradbury. I will open a new document. I put a word or two where the title would be, and I just start writing about it. Eventually, a story begins and I follow it. There is no planning or outlining. There are fingertips to keys and stream of consciousness guiding them. This has been very effective for me in the past. Your brain knows what to write, as long as you don’t get in the way of it too much.

I am extremely interested in dramatic and writing theory. Three act structures, protagonists, antagonists, the relationships between subplots and character arcs. It is really sickening, in some ways. If I can get my hands on a writing book, I read it. John Garner has a collection of them. The Art of Fiction, On Moral Fiction, and On Becoming a Novelist all sit on my desk. Aristotle’s Poetics has been a required tome for screenwriters, but all writers could learn something from his notes on dramatic theory.

Some of that stuff gets absorbed into my psyche, and I begin to do it naturally, without thinking. But some of it comes during the re-writing phase. Does my protagonist change? Do I have a strong conflict with my plot constantly driving to answer the story question? Do my sub-plots add to my story by complicating things further for my protagonist, or do they distract from my major plot, or even overwhelm it? I have to ask myself all of this and more. Re-writing is a very conscious process, and you have to bring your logical brain in to it, even if it hurts.

Sometimes it does hurt. It seems like there are a million rules out there about how writing is supposed to happen. The thing to remember is that you don’t have to use all of them. The number one truth in writing is that if it works it is correct. Every rule has been successfully broken at one time or another. The important thing is that you pick up enough technique and theory that you become a dangerous weapon. You are James Bond. You have a million fancy gadgets to utilize, but you must complete your mission, and you must get the girl.

A writer is like a puzzle. You see all these pieces laying on the table, and they don’t appear to be in any sort of order. But when you piece them altogether, you get the big picture. Some of my big influences are some of my favorite writers, but that doesn’t really matter. They just have to be another piece that fits into the puzzle that is me.

All the great writers, even all the bad writers, lift you up and carry you farther than you might have gone on your own. Jump up on their backs and maybe you will see something new. Try something they tried, and then take it farther. Break rules, bend theory, or use them religiously. Just make it work.